I’m always looking for ways to expand my clientele’s understanding of and appreciation for fine jewelry. I enjoy helping a customer realize the value of the truly rare and spectacular things of the world. There’s a sense of accomplishment that comes with educating consumers on how to properly care for their fine jewelry investments so they get the years of pleasure out of them that they should.

As you’ve doubtless figured out over the last few blog posts, I think pearls are just wonderful. They represent a magnificent portion of the world of fine jewelry to which there is far more than many people may be aware.

“Pearl” generally refers to the organic gem material created by certain varieties of oysters and mussels, but almost all shelled mollusks produce what are called “calcareous concretions.” So long as they are naturally formed by wild mollusks, the US Federal Trade Commission and the World Jewelry Council have deemed that any of these calcareous concretions may be called “pearls,” or “non-nacreous pearls” if more concise terminology is required.

So what does “non-nacreous” mean? Well, nacre is what gives oyster, mussel, and abalone pearls their luster and iridescence. It’s a combination of the mineral aragonite and a protein called conchiolin; nacre is basically the fancy name for mother-of-pearl. But not all mollusks produce nacre, and so their pearls are considered non-nacreous, or “porcelaneous.” These pearls do not have an iridescent surface, but a highly glossy surface – like porcelain – and some of them exhibit beautiful colors and optical effects.

The pearls from most other mollusks hold no value beyond being a novelty, and many are not stable enough to be used in jewelry. There are a few, though, that are highly sought after rarities with exceptional worth. While all naturally occurring pearls in wild mollusks are rare, certain non-nacreous pearls of gem quality are considerably rarer than even wild South Seas or Tahitian pearls.

Some types of these pearls you might be interested in are:

Queen conch pearls show a remarkable and gorgeous chatoyance called “flame structure.”

Queen conch pearl showing excellent flame structure

Horse conch pearls, which can also show flame structure.

Various horse conch pearls

Blue mussel pearls can sometimes be naturally vivid blue.

Collection of blue mussel pearls. Image courtesy of bluemusselpearls.blogspot.no

Pacific lion’s paw scallop pearls are typically found in rich colors most other pearls must be dyed to achieve, like salmon, maroon, red, or even deep purple.

Lion’s paw scallop pearl

Quahog clam pearls are among the rarest and most expensive natural pearls in the world.

Suites of Quahog pearls. Image courtest of www.pearl-guide.com

The astoundingly rare and unusually large Melo Melo pearl from the baler snail, which is technically not a mollusk at all, but a gastropod. One of these pictures features a 145-carat round Melo Melo pearl –over an ounce; that’s a whole lotta’ anything in jewelry terms. Singular pearls like this can command prices in excess of $50,000.

Now, this blog isn’t necessarily a sales pitch. I don’t have any of these alternative pearls in stock, although I can certainly track them down for you, if you’re seriously interested in owning them. This is one of those informative pieces designed to expose you to cool stuff you probably wouldn’t hear about elsewhere.

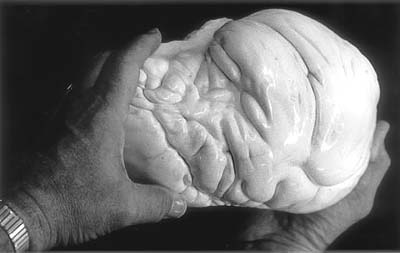

Just prove it, here’s a picture of the largest pearl ever discovered, produced by a giant clam: The Pearl of Lao Tzu. It’s not particularly attractive, but it is the size of an infant, which I think is pretty impressive.

Pearl of Lao Tzu.

Tags: blog, blue mussel pearls, colors, fine jewelry, horse conch pearls, Lao Tzu, lions paw scallop pearl, Melo Melo, melo melo pearl, mollusks, pearl of Lao Tzu, pearls, quahog clam pearls, queen conch pearl